Living a Pious True life

0 comments Published by Panna Padipa-Light of Wisdom and Compassion on Wednesday, April 11, 2007 at 11:12 PM心犹如相续的河流,假如你无法运用你的修持来把握它的每个当下,你做的持咒,观想,念诵,禅修,乃至谈吐高超的见地,显现高超的行为,这些都是在浪费时间。

修行的本质并没有任何奇特的地方,它的实质就是反复的深入我们的心相续,并且改变它,否则,这个宝贵的人身会被浪费,你用一生的时间追逐自己的念头,执着它所创造的轮回,实际上,就是在梦幻中迷失自己而不自觉。

每天从细微的小处着手,不要奢望神奇的辉煌,看穿这些虚荣的把戏,仔细观察自己的心吧。即使在今生,你无法彻底转化你的心,你无法在证悟上取得多大的进展,只要你很小心的守护自己的三业,照顾自己的每一个念头,虽然你无法达到甚至是在睡眠中清醒,或是在重病还能控制自己的心,但是只要你努力的修自己每个念头,努力而虔诚的对待自己彻底的内在,而不是做外表的样子,那么,就好象曲吉旺波在《大圆满三要释吉祥王》中所唱的那样:“即使此生不成就,也内心安详真愉快。”为什么呢?从内在的层次,你已经转化了你的心,从而转化了你的生命,安详、慈悲、放下,已经展示出最大的成就。

成就分为外在的,内在的,秘密的,极其秘密的。就外在的成就层面,先是心智的成就,但是你虽然掌握了伟大的知识,了解了高深的见地,但是很不幸,它们就好象是在衣服上的补丁,终究会要脱落。例如,我们在健康的时候会感到很自在,而且我们拥有佛法的知识,这一切以一种良好的自我感来暗示:似乎我们是不凡的圣哲,但是,当你遇到重病的时候,你浑身火烧而陷入昏迷,仔细看你的心吧,它根本不受到你的控制,种种接近死亡的业相在梦中显示,即使你厌恶他们而不敢堕入昏睡,但昏迷会迅速将你击垮,哪个时候,你的任何才智,学问,都帮助不了你,于是,修行人应该知道,在重病中出现世俗乃至恐怖的持续梦境,这是修行的耻辱,甚至,这是闻思的耻辱,没有投入修行,或是表面的修行,这是镜子上的雾气,维持不了多久。

其次是验修的成就,当喜悦和光明产生,巨大的宁静伴随深沉的陶醉,甚至可以看到各色奇异的景象,并且能预先知道事情的发生,这些体验就好象对山谷大声叫喊一样,你努力的叫喊,它给你很大的回音,但是随即就消失了。假如你努力的修持,各种奇特的经验发生了,但是记住,这世界上的一切都不免无常,假如你想拥有这些体验,永恒的占有它们,那么,你就会经受好似捕捉水中的月亮一样的痛苦,它们根本就是无常,所以从验修的种种幻想中解脱吧,不企图占有它们,平等的看待它们,而不扰乱内在的心相续,哪怕是在广大的平等定见中,一切显现为不实际的五色烟雾或虹光,而能自在的穿越墙壁或是在岩石上按下手印,但将这些视为开悟的标志并产生我慢,这是着魔的开始,并因为我执而流浪轮回。

最后是广大的明智成就,这预示着我们平等的对待生活,安然的安住在广大的心性中,一切都成为庄严的自然解脱,于自心的智慧中,消除了执着和烦恼,慈悲并心胸宽广,生活之中任何的事物都无法搅乱这内在的明智,超越喜悦和悲哀,安然的任运于当下。

经由心的修持,我们经历各个不同的阶段,最终,我们的心成为空与光明的一味,任何恐惧或是希冀,都无法占据我们的心灵,这就是佛陀之道。

Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche

圣开法师答

问:

请示师傅,要怎样修治散乱的心?

答:

要修散乱的心,就要修不散乱。现在你们把眼睛闭上,手合掌,师傅现在就教你们修。这个时候你心里面什么都不想,散乱心就没有了。(数分钟)

好,现在眼睛睁开,师傅教你们的就是修禅定。你把这个杂乱妄想的心收回来,置心一处,无事不办,把这个心定在不动的地方,不动就是定,定了以后,智慧也就会生出来了。

但是修禅定最要紧的是要有觉,有很多人学佛修行,念佛参禅一辈子,他没有智慧,原因就是没有觉。所以我们把这个心定在一处以后,我们还要有一种觉观,觉照。觉就是你这个心不动,有一微尘飞过你都知道,那么这个定就差不多了。

谈到觉,假使你不但觉了自己的心,他方世界开了一朵花,都好像在你的手里边一样,看得清清楚楚,那么你就成佛了。

所以这个修法是很不简单,师傅这么简单就跟你们讲了,大家要珍惜。

Source: Xin Fu Wen Hua, Volume 30, April 2007 Series

Following Q&A by Missionary Chen Ming An, a dharma successor of Venerable Shen Kai (founder of Wei Fo Zhong, Buddhahood Sect/Buddha-Only Sect)

http://www.dailyzen.com/zen/zen_reading34.asp

The Mind Ground - T'aego

At the behest of the King, T'aego gave a brief outline of the basic principles of Zen:

There is something bright and clear, without falsity, without biases, tranquil and unmoving, possessed of vast consciousness, fundamentally without birth and death and discrimination, without names and forms and words. It engulfs space and covers all of heaven and earth, all of form and sound, and is equipped to function.

If we speak of its essence, it is so vast it embraces everything, so that nothing is outside of it. If we speak about its function... even great sages cannot get to the end of it.

This one thing is always with each and every person. Whether you move or not, whenever you encounter circumstances and objects, it is always very obvious and clear, clear everywhere, revealed in everything. It is quietly shining in all activities. As an expedient, it is called Mind. It is also called the Path, and the king of the myriad dharmas, and Buddha. Buddha said that whether walking, sitting or lying down, we are always within it.

Even Yao and Shun said: "Holding faithfully to the mean, without contrived activity, everything under heaven is well ordered." Weren't Yao and Shun sages? Weren't the buddhas and enlightened teachers special people? They simply managed to illuminate This Mind.

Therefore, since antiquity, the buddhas and enlightened teachers have never established words and texts as sacred: they just transmitted Mind with Mind, without any other separate teaching. If there is some other teaching outside This Mind, this is a deluded theory, not the words of the Buddha. Thus, when we use the name Mind, it is not the ordinary person's mind that falsely engenders discrimination: rather, it is the silent and motionless Mind in each person.

People cannot preserve this inherent Mind for themselves. Unwittingly they make false moves and are suddenly thrown into confusion by the wind of objects: they are buried in sensory experiences, which arise and disappear again and again. They falsely create the karmic suffering of endless birth and death. Therefore, the buddhas and enlightened teachers and sages appeared in the world by the power of their past bodhisattva vows. They use great compassion and directly point out that the human mind is inherently enlightened, and they enable people to awaken to the mind-buddha.

Your majesty must contemplate his own inherent mind. During lulls in the myriad functions of state, Your Majesty should sit upright in the palace, without thinking of good and evil at all, just like a golden statue of Buddha. Then the false thinking of birth and destruction is totally obliterated and the obliterating is obliterated, in an instant the mindground is quiet and motionless, with nothing to rest on. Body and mind are suddenly empty: it's like leaning on the void. All that appears here is total clarity and illumination.

At this moment you should look carefully at your original face before your father and mother were born. As soon as it is brought up, you awaken to it: then like a person drinking water, you know yourself whether it is cool or warm. It cannot be described or explained to anyone else. It's just a luminous awareness covering heaven and earth.

When the realm I've just talked about spontaneously appears before you, you will have no doubts about birth and death, you will have no doubts about the sayings of the buddhas and enlightened teachers- indeed, you will have met the buddhas and enlightened teachers. This is the wonder transmitted from person to person by buddhas and enlightened teachers since antiquity.

You must make it your concern: be careful not to neglect it. Be like this even when attending to affairs of state and working for the renovation of the people. Use this Path also to be alert to all events and to encourage all our ministers and common subjects to share together in the uncontrived inner truth and enjoy Great Peace. Then the buddhas are sure to rejoice.

- T'aego (1301-1382)

Taken from A Buddha from Korea: The Zen Teachings of T'aego, Thomas Cleary (1988)

--------------------------------

We no longer live in times where leaders ask Zen masters for guidance nor where true guidance is that easily attainable. However, to one who is sincerely trying to cultivate the "mind that seeks the Way" the tradition is still alive and worth finding. To understand how to maintain practice throughout one's daily life is the koan for many of today's students. That is at heart what T'aego is offering to the King in the excerpt above, how to realize Mind in everyday activities. Sometimes using language at all to communicate becomes the main barrier, then we have the language of ages past and the situation becomes more abstruse. In more recent times this same message was communicated in the following:

*

You can be your own sage. You can be your own teacher if you are a person for whom no task is worth losing the Way. No goal, no thing, nothing you are doing, is really worth throwing that awareness away for. No feeling that you have is as important as staying at that cool, clear center of awareness. If you are going to move like a fly buzzing around, or you are going to be oppressed by a thought or feeling that comes up, where is your love of the Way then? Where is your love of the Way when you are buzzing around? That is when you have to keep coming back and find it.

This takes a tremendous effort. A tremendous amount of energy is all that it takes the next time you feel that way. It is like pushing your way through to your second wind. The next time that you have a feeling oppressing you, stand up, observe and use every atom of energy you have to observe. Don't just sit there and let it push you to the ground.

To be that still, clear mind everyday is the only thing that makes life truly worth living. The rest is just gaining, winning, and losing. You should put every atom into living these principles -- to realize them, to see them, to use them.

Everything you do is from Blue Sky Mind. You don't run off with your delusions when they arise. You see them as clouds. You understand that which stays and that which goes. This consciousness that you have, the Blue Sky Mind observes all these states and sees them all clearly.

- Taken from unpublished manuscripts of Traceless Way

Returning to Blue Sky Mind,

The Monkess

http://www.dailyzen.com/zen/zen_reading0611.asp From the Record of Things Heard Dogen (1200-1253)

One day a student asked: “I have spent months and years in earnest study, but I have yet to gain enlightenment. Many of the old masters say that the Way does not depend on intelligence and cleverness, and that there is no need for knowledge and talent. As I understand it, even though my capacity is inferior, I need not feel badly for myself. Are there not any old sayings or cautionary words that I should know about?” Dogen replied: “Yes, there are. True study of the Way does not rely on knowledge and genius or cleverness and brilliance. Because study has no use for wide learning and high intelligence, even those with inferior capacities can participate. True study of the Way is an easy thing. Even in the monasteries of China, only one or two out of several hundred, or even a thousand, disciples under a great Ch’an master actually gained true enlightenment. Therefore, old sayings and cautionary words are needed. As I see it now, it is a matter of gaining the desire to practice. A person who gives rise to a real desire and puts his utmost efforts into study will surely gain enlightenment. Essentially, one must devote all attention to this effort and enter into practice with all due speed. More specifically, the following points must be kept in mind: “In the first place, there must be a keen and sincere desire to seek the Way. For example, someone who wishes to steal a precious jewel, to attack a formidable enemy, or to make the acquaintance of a beautiful woman must, at all times, watch intently for the opportunity, adjusting to changing events and shifting circumstances. Anything sought for with such intensity will surely be gained. If the desire to search for the Way becomes as intense as this, whether you concentrate on doing zazen alone, investigate a koan by an old master, interview a Zen teacher, or practice with sincere devotion, you will succeed no matter how high you must shoot or no matter how deep you must plumb. “Without arousing this wholehearted will for the Buddha Way, how can anyone succeed in this most important task of cutting the endless round of birth and death? Those who have this drive, even if they have little knowledge or are of inferior capacity, even if they are stupid or evil, will without fail gain enlightenment. “Next, to arouse such a mind, one must be deeply aware of the impermanence of the world. This realization is not achieved by some temporary method of contemplation. It is not creating something out of nothing and then thinking about it. Impermanence is a fact before our eyes. Do not wait for the teachings from others, the words of the scriptures, and for the principles of enlightenment. We are born in the morning and die in the evening; the person we saw yesterday is no longer with us today. These facts we see with our own eyes and hear with our own ears. You see and hear impermanence in terms of another person, but try weighing it with your own body. “Even though you live to be seventy or eighty, you die in accordance with the inevitability of death. How will you ever come to terms with the worries, joys, intimacies, and conflicts that concern you in this life? With faith in Buddhism, seek the true happiness of nirvana. How can those who are old or who have passed the halfway mark in their lives relax in their studies when there is no way of telling how many years are left?” Think of those who gained enlightenment upon hearing the sound of bamboo when struck by a tile or seeing blossoms in bloom. Does the bamboo distinguish the clever or dull, the deluded or enlightened; does the flower differentiate between shallow and deep, the wise and stupid? Though flowers bloom The most important point in the study of the Way is zazen. Many people in China gained enlightenment solely through the strength of zazen. Some who were so ignorant that they could not answer a single question exceeded the learned who had studied many years solely through the efficacy of their single-minded devotion to zazen. Therefore, students must concentrate on zazen alone and not bother about other things. The Way of the Buddhas and Ancestors is zazen alone. Follow nothing else. At that time Ejo asked: “When we combine zazen with the reading of the texts, we can understand about one point in a hundred or a thousand upon examining the Zen sayings and koans. But in zazen alone there is no indication of even this much. Must we devote ourselves to zazen even then?” Dogen answered: “Although a slight understanding seems to emerge from examining a koan, it causes the Way of the Buddhas and Ancestors to become even more distant. If you devote your time to doing zazen without wanting to know anything and without seeking enlightenment, this is itself the Ancestral Way. Although the old Masters urged both the reading of the scriptures and the practice of zazen, they clearly emphasized zazen. Some gained enlightenment through the koan, but the merit that brought enlightenment came from the zazen. Truly the merit is in the zazen.” The basic point to understand in the study of the Way is that you must cast aside your deep-rooted attachments. If you rectify the body in terms of the four attitudes of dignity, the mind rectifies itself. Students, even if you gain enlightenment, do not stop practicing, thinking that you have attained the ultimate. The Buddha Way is endless. Once enlightened you must practice all the more.

Dogen (1200-1253)

Excerpted from The Roaring Stream - A New Zen Reader Edited by Nelson Foster and Jack Shoemaker 1996 * One of the challenges to a life of practice is to protect and nourish the Mind that seeks the Way. In the beginning it is easy to have the intensity of Beginner’s Mind; everything is so fresh, so vital, so exotic sounding. Here, though, a student is questioning Dogen about his lack of attaining enlightenment, a feeling many in practice experience from time to time. Dogen answers by assuring him that anything you devote your energy to with intensity and sincere desire will over time bear fruits for your labor. Later on he answers more directly by stating: “If you devote your time to doing zazen without wanting to know anything and without seeking enlightenment, this is itself the Ancestral Way.” At some point in training sitting is just enough in and of itself; the “goals” of practice take more of a back seat. Meditation is just sitting in the lap of the universe and expressing your nature. All of us have our own genjo koans, or life questions that help to keep practice vital. To settle for answers to unanswerable questions dulls the mind and practice. To live with our questions each day, to see them in our lives, and to see them evolve into new questions keeps the practice “keen and sincere.”

May your Way Be Clear, Elana, Monkess for Daily Zen | |

| | |

| |

Repentance Sutra recommendation

0 comments Published by Panna Padipa-Light of Wisdom and Compassion on Tuesday, March 6, 2007 at 11:47 AM

大通方广忏悔灭罪庄严成佛经

also named 大解脱经

url link :

http://bbs.ningma.com/dispbbs.asp?boardID=9&ID=327&page=3

《大通方广忏悔灭罪庄严成佛经》

这部经文的缘起本身就极具殊胜加持力,感人泪下。它是我们的本师释迦世尊去娑罗树涅盘途中宣讲的经文。

释迦世尊临欲涅盘的时候,心中仍充满了对我们罪苦众生的极大悲悯,再赐净除罪障的方便,教令称念十方三世佛和菩萨名号以及十二部经名。

這部經文的緣起本身就極具殊勝加持力,感人淚下。它是我們的本師釋迦世尊去娑羅樹涅槃途中宣講的經文。釋迦世尊臨欲涅槃的時候,心中仍充滿了對我們罪苦眾生的極大悲憫,再賜淨除罪障的方便,教令稱念十方三世佛和菩薩名號以及十二部經名。另外,本經內容十分豐富:不僅宣講了懺悔淨罪的殊勝法門,包括參加修持的人數、天數和占夢的驗相等,還宣講了三乘是一乘、別相三寶、一相三寶、薦拔眾生的方便、無上空義、成就菩薩道的方便、佛的本生故事、對虛空藏菩薩的授記等等。經中講,此經比佛更難值遇。我們的本師釋迦佛曾經歷劫修行,供養無數諸佛,但僅僅得聞一次此經的名字,並未親眼得見此經。而後又經多劫修行,終於定光佛時得聞得見此經

這部歷史上曾僅存名字的經典,一百年前終於振落掉了敦煌藏經洞千年的塵封,它先輾轉飄零於異國他鄉,而後又在它的故土上與房山石經洞的藏經完整地會聚一處,最終在大悲上師三寶的覆護之下,漢地眾生從藏傳佛教系統又重新接續上了《大通方廣懺悔滅罪莊嚴成佛經》殊勝的無間斷的傳承加持,使《大通方廣懺悔滅罪莊嚴成佛經》的法門得到了再次的弘揚,無量的眾生將因此而證得解脫┄┄。每當想起所有的這一切,心中就湧起了對大悲上師三寶無限的感恩與思念┄┄。

感动涕零

by Toni Packer

by Toni PackerAre we interested in exploring this amazing affair of ‘myself’ from moment to moment?

A somber day, isn't it? Dark, cloudy, cool, moist and windy. Amazing, this whole affair of the weather!

We call it weather, but what is it really? Wind. Rain. Clouds slowly parting. Not the words spoken about it, but just this darkening, blowing, pounding and wetting, and then lightening up, blue sky appearing amid darkness, and sunshine sparkling on wet grasses and leaves. In a little while there'll be frost, snow and ice covers. And then warming again, melting, oozing water everywhere. On an early spring day the dirt road sparkles with streams of wet silver. So—what is weather other than this incessant change of earthly conditions and all the human thoughts, feelings and undertakings influenced by it? Like and dislike. Depression and elation. Creation and destruction. An ongoing, ever-changing stream of happenings abiding nowhere. No real entity weather exists anywhere except in thinking and talking about it.

Now, is there such an entity as me or I? Or is it just like the weather—an ongoing, ever-changing stream of ideas, images, memories, projections, likes and dislikes, creation and destruction, that thought keeps calling I, me, Toni, and thereby solidifying what is evanescent? What am I really, truly, and what do I merely think and believe I am?

Are we interested in exploring this amazing affair of myself from moment to moment? Is this, maybe, the essence of this work? Exploring ourselves attentively, beyond the peace and quiet that we are seeking and maybe finding occasionally? Coming upon an amazing insight into this deep sense of separation that we call me and other people, me and the world, without any need to condemn or overcome?

Most human beings take it for granted that I am me, and that me is this body, this mind, this knowledge and sense of myself that feels so obviously distinct and separate from other people and from the nature around us. The language in which we talk to ourselves and to each other inevitably implies separate me's and you's all the time. All of us talk I-and-you talk. We think it, write it, read it, and dream it with rarely any pause. There is incessant reinforcement of the sense of me, separate from others. Isolated, insulated me. Not understood by others. How are we to come upon the truth if separateness is taken so much for granted, feels so commonsense?

The difficulty is not insurmountable. Wholeness, our true being, is here all the time, like the sun behind the clouds. Light is here in spite of cloud cover.

What makes up the clouds?

Can we begin to realize that we live in conceptual, abstract ideas about ourselves? That we are rarely in touch directly with what actually is going on? Can we realize that thoughts about myself—I'm good or bad, I'm liked or disliked—are nothing but thoughts, and that thoughts do not tell us the truth about what we really are? A thought is a thought, and it triggers instant physical reactions, pleasures and pains throughout the bodymind. Physical reactions generate further thoughts and feelings about myself—"I'm suffering," "I'm happy," "I'm not as bright, as good-looking as the others."

That feedback implies that all this is me, that I have gotten hurt, or feel good about myself, or that I need to defend myself or get more approval and love from others. When we're protecting ourselves in our daily inter-relationships we're not protecting ourselves from flying stones or bomb attacks. It's from words we're taking cover, from gestures, from coloration of voice and innuendo.

"We're protecting ourselves, we're taking cover." In using our common language the implication is constantly created that there is someone real who is protecting and someone real who needs protection.

Is there someone real to be protected from words and gestures, or are we merely living in ideas and stories about me and you, all of it happening in the ongoing audio/video drama of ourselves?

The utmost care and attention is needed to see the internal drama fairly, accurately, dispassionately, in order to express it as it is seen. What we mean by "being made to feel good" or "getting hurt" is the internal enhancing of our ongoing me-story, or the puncturing and deflating of it. Enhancement or disturbance of the me-story is accompanied by pleasurable energies or painful feelings and emotions throughout the organism. Either warmth or chill can be felt at the drop of a word that evokes memories, feelings, passions. Conscious or unconscious emotional recollections of what happened yesterday or long ago surge through the bodymind, causing feelings of happiness or sadness, affection or humiliation.

Right now words are being spoken, and they can be followed literally. If they are fairly clear and logical they can make sense intellectually. Perhaps at first it's necessary to understand intellectually what is going on in us. But that's not completely understanding the whole thing. These words point to something that may be directly seen and felt, inwardly, as the words are heard or read.

As we wake up from moment to moment, can we experience freshly, directly, when hurt or flattery is taking place?

What is happening? What is being hurt? And what keeps the hurt going?

Can there be some awareness of defenses arising, fear and anger forming, or withdrawal taking place, all accompanied by some kind of story-line? Can the whole drama become increasingly transparent? And in becoming increasingly transparent, can it be thoroughly questioned? What is it that is being protected? What is it that gets hurt or flattered? Me? What is me? Is it images, ideas, memories?

It is amazing. A spark of awareness witnessing how one spoken word arouses pleasure or pain throughout the bodymind. Can the instant connection between thought and sensations become palpable? The immediacy of it. No I-entity directing it, even though we say and believe I am doing all that. It's just happening automatically, with no one intending to "do" it. Those are all afterthoughts!

We say, "I didn't want to do that," as though we could have done otherwise. Words and reaction proceed along well-oiled pathways and interconnections. A thought about the loss of a loved one comes up and immediately the solar plexus tightens in pain. Fantasy of lovemaking occurs and an ocean of pleasure ensues. Who does all that? Thought says, "I do. I'm doing that to myself."

To whom is it happening? Thought says, "To me, of course!"

But where and what is this I, this me, aside from all the thoughts and feelings, the palpitating heart, the painful and pleasurable energies circulating throughout the organism? Who could possibly be doing it all with such amazing speed and precision? Thinking about ourselves and the triggering of physiological reactions takes time, but present awareness brings the whole drama to light instantly. Everything is happening on its own. No one is directing the show!

Right at this moment wind is storming, windows are rattling, tree branches are creaking, and leaves are quivering. It's all here in the listening—but whose listening is it? Mine? Yours? We say, "I'm listening," or, "I cannot listen as well as you do," and these words befuddle the mind with feelings and emotions learned long ago. You may be protesting, "My hearing isn't yours. Your body isn't mine." We have thought like that for eons and behave accordingly; but at this moment can there be just the sound of swaying trees and rustling leaves and fresh air from the open window cooling the skin? It's not happening to anyone. It's simply present for all of us, isn't it?

Do I sound as though I'm trying to convince you of something? The passion arising in trying to communicate simply, clearly, may be mistaken for a desire to influence people. That's not the case. There is just the description of what is happening here for all of us. Nothing needs to be sold or bought. Can we simply listen and investigate what is being offered for exploration from moment to moment?

What is the me that gets hurt or flattered, time and time again, the world over? In psychological terms we say that we are identified with ourselves. In spiritual language we say that we are attached to ourselves. What is this ourselves? Is it feeling of myself existing, knowing what I am, having lots of recollections about myself—all the ideas and pictures and feelings about myself strung together in a coherent story? And knowing this story very well—multitudes of memories, some added, some dropped, all interconnected—what I am, how I look, what my abilities and disabilities are, my education, my family, my name, my likes and dislikes, opinions, beliefs, and so on. The identification with all of that, which says, "This is what I am." And the attachment to it, which says, "I can't let go of it."

Let' s go beyond concepts and look directly into what we mean by them. If one says, "I'm identified with my family name," what does that mean? Let me give an example. As a growing child I was very much identified with my last name because it was my father's and he was famous, so I was told. I liked to tell others about my father's scientific achievements to garner respect and pleasurable feelings for myself by impressing friends. I felt admiration through other people's eyes. It may not even have been there. It may have been projected. Perhaps some people even felt, "What a bore she is!" On the entrance door to our apartment there was a little polished brass plate with my father's name engraved on it and his titles: "Professor Doctor Phil." The "Phil" impressed me particularly, because I thought it meant that my father was a philosopher, which he was not. I must have had the idea that a philosopher was a particularly imposing personage. So I told some of my friends about it and brought them to look at the little brass sign at the door.

This is one meaning of identification: enhancing one's sense of self by incorporating ideas about other individuals or groups, or one's possessions, achievements or transgressions, anything, and feeling that all of this is me. Feeling important about oneself generates amazingly addictive energies.

To give another example from the past: I became very identified with my half-Jewish descent. Not openly in Germany, where I mostly tried to hide it rather than display it, but later on after the war ended, telling people of our family' s fate and finding welcome attention, instant sympathy, and nourishing interest in the story. One can become quite addicted to making the story of one's life impressive to others and to oneself, and feed on the energies aroused by that. And when that sense of identification and attachment is disturbed by someone not buying into it, contesting it, or questioning it altogether, there is sudden insecurity, physical discomfort, anger, fear and hurt.

Becoming a member of a Zen center and engaging in spiritual practice, I realized one day that I had not been talking about my background in a long while. And now, when somebody brings it up—sometimes an interviewer will ask me to talk about it—it feels like so much bother and effort. Why delve into old memory stuff? I want to talk about listening, the wind, and the birds.

Are we listening right now? Or are we more interested in identities and stories?

We all love stories, don't we? Telling them and hearing them is wonderfully entertaining.

At times people wonder why I don't call myself a teacher when I'm so obviously engaged in teaching. Somebody actually brought it up this morning—the projections and the associations aroused in waiting outside the meeting room and then entering nervously with a pounding heart. Do images of teacher and student offer themselves automatically like clothes to put on and roles to play in these clothes? In giving talks and meeting with people the student-teacher imagery does not have to be there; it belongs to a different level of existence. If images do come up, they're in the way, like clouds hiding the sun. Relating without images is the freshest, freest thing in the universe.

So, what am I and what are you? What are we without images clothing and hiding our true being? It's un-image-inable, isn't it? And yet there's the sound of wind blowing, trees shaking, crows cawing, woodwork creaking, breath flowing without need for any thoughts. Thoughts are grafted on top of what's actually going on right now, and in that grafted world we happen to spend most of our lives.

Yet every once in awhile, whether one does meditation or not, the real world shines wondrously through everything. How is it when words fall silent? When there is no knowing? When there is no listener and yet there is listening, awaring in utter silence?

The listening to, the awaring of the me-story is not part of the me. Awareness is not part of that network. The network cannot witness itself. It can think about itself and even change itself, establish new behavior patterns, but it cannot see itself or free itself. There is a whole psychological science called behavior modification that, through reward and punishment, tries to drop undesirable habits and adopt better, more sociable ones. This is not what we're talking about. The seeing, the awaring of the me movement is not part of the me movement.

A moment during a visit with my parents in Switzerland comes to mind. I had always had a difficult relationship with my mother. I had been afraid of her. She was a very passionate woman with lots of anger, but also love. Once during that visit I saw her standing in the dining room facing me. She was just standing there, and for no known reason I suddenly saw her without the past. There was no image of her, and also no idea of what she saw in me. All that was gone. There was nothing left except pure love for this woman. Such beauty shone out of her. And our relationship changed; there was a new closeness. No one changed it. It just happened.

Truly seeing is freeing beyond imagination.

Toni Packer began studing Zen in 1967 with Roshi Philip Kapleau at the Rochester Zen Center. In 1981, she founded the Springwater Center for Meditative Inquiry in Springwater, New York. From The Wonder of Presence and the Way of Meditative Inquiry, by Toni Packer. Published by Shambhala Publications. © 2003 by Toni Packer.

Essentials of Practice and Enlightenment for Beginners

0 comments Published by Soh on Sunday, February 11, 2007 at 7:55 PM By Master Hanshan Deqing [1546-1623]

Translation by Guo-gu Shi

I. How to Practice and Reach Enlightenment

Concerning the causes and condition of this Great Matter, [this Buddha-nature] is intrinsically within everyone; as such, it is already complete within you, lacking nothing. The difficulty is that, since time without beginning, seeds of passion, deluded thinking, emotional conceptualizations, and deep-rooted habitual tendencies have obscured this marvelous luminosity. You cannot genuinely realize it because you have being wallowing in remnant deluded thoughts of body, mind, and the world, discriminating and musing [about this and that]. For these reason you have been roaming in the cycle of birth and death [endlessly]. Yet, all Buddhas and ancestral masters have appeared in the world using countless words and expedient means to expound on Chan and to clarify the doctrine. Following and meeting different dispositions [of sentient being], all of these expedient means are like tools to crush our mind of clinging and realize that originally there is no real substantiality to "dharmas" or [the sense of] "self."

What is commonly known as practice means simply to accord with [whatever state] of mind youíre in so as to purify and relinquish the deluded thoughts and traces of your habit tendencies. Exerting your efforts here is called practice. If within a single moment deluded thinking suddenly ceases, [you will] thoroughly perceive your own mind and realize that it is vast and open, bright and luminousóintrinsically perfect and complete. This state, being originally pure, devoid of a single thing, is called enlightenment. Apart from this mind, there is no such thing as cultivation or enlightenment. The essence of your mind is like a mirror and all the traces of deluded thoughts and clinging to conditions are defiling dust of the mind. Your conception of appearances is this dust and your emotional consciousness is the defilement. If all the deluded thoughts melt away, the intrinsic essence will reveal in its own accord. Itís like when the defilement is polished away, the mirror regains its clarity. It is the same with Dharma.

However, our habit, defilement, and self-clinging accumulated throughout eons have become solid and deep-rooted. Fortunately, through the condition of having the guidance of a good spiritual friend, our internal prajna as a cause can influence our being so this inherent prajna can be augmented. Having realized that [prajna] is inherent in us, we will be able to arouse the [Bodhi-] mind and steer our direction toward the aspiration of relinquishing [the cyclic existence of] birth and death. This task of uprooting the roots of birth and death accumulated through innumerable eons all at once is a subtle matter. If you are not someone with great strength and ability brave enough to shoulder such a burden and to cut through directly [to this matter] without the slightest hesitation, then [this task] will be extremely difficult. An ancient one has said, "This matter is like one person confronting ten thousand enemies." These are not false words.

II. The Entrance to Practice and Enlightenment

Generally speaking, in this Dharma-ending-age, there are more people who practice than people who truly have realization. There are more people who waste their efforts than those who derive power. Why is this? They do not exert their effort directly and do not know the shortcut. Instead, many people merely fill their minds with past knowledge of words and language based on what they have heard, or they measure things by means of their emotional discriminations, or they suppress deluded thoughts, or they dazzle themselves with visionary astonishment at their sensory gates. These people dwell on the words of the ancient ones in their minds and take them to be real. Furthermore, they cling to these words as their own view. Little do they know that none of these are the least bit useful. This is what is called, "grasping at otherís understanding and clouding oneís own entrance to enlightenment."

In order to engage in practice, you must first sever knowledge and understanding and single-mindedly exert all of your efforts on one thought. Have a firm conviction in your own [true] mind that, originally it is pure and clear, without the slightest lingering thingóit is bright and perfect and it pervades throughout the Dharmadhatu. Intrinsically, there is no body, mind, or world, nor are there any deluded thoughts and emotional conceptions. Right at this moment, this single thought is itself unborn! Everything that manifests before you now are illusory and insubstantialóall of which are reflections projected from the true mind. Work in such a manner to crush away [all your deluded thoughts]. You should fixate [your mind] to observe where the thoughts arise from and where they cease. If you practice like this, no matter what kinds of deluded thoughts arise, one smash and they will all be crushed to pieces. All will dissolve and vanish away. You should never follow or perpetuate deluded thoughts. Master Yongjia has admonished, "One must sever the mind [that desires] continuation." This is because the illusory mind of delusion is originally rootless. You should never take a deluded thought as real and try to hold on to it in your heart. As soon as it arises notice it right away. Once you notice it, it will vanish. Never try to suppress thoughts but allow thoughts to be as you watch a gourd floating on water.

Put aside your body, mind, and world and simply bring forth this single thought [of method] like a sword piercing through the sky. Whether a Buddha or a Mara appears, just cut them off like a snarl of entangled silk thread. Use all your effort and strength patiently to push your mind to the very end. What is known as, "a mind that maintains the correct thought of true suchness" means that a correct thought is no-thought. If you are able to contemplate no-thought, youíre already steering toward the wisdom of the Buddhas.

Those who practice and have recently generated the [Bodhi-] mind should have the conviction in the teaching of mind-only. The Buddha has said, "The three realms are mind-only and the myriad dharmas are mere consciousness." All Buddhadharma is only further exposition on these two lines so everyone will be able to distinguish, understand, and generate faith in this reality. The passages of the sacred and the profane, are only paths of delusion and awakening with in your own mind. Besides the mind, all karmas of virtue and vice are unobtainable. Your [intrinsic] nature is wondrous. It is something natural and spontaneous, not something you can "enlighten to" [since you naturally have it]. As such, what is there to be deluded about? Delusion only refers to your unawareness that your mind intrinsically has not a single thing, and that the body, mind, and world are originally empty. Because youíre obstructed, therefore, there is delusion. You have always taken the deluded thinking mind, that constantly rises and passes away, as real. For this reason, you have also take the various illusory transformations in and appearances of the realms of the six sense objects as real. If today you are willing to arouse your mind and steer away from [this direction] and take the upper road, then you should cast aside all of your previous views and understanding. Here not a single iota of intellectual knowledge or cleverness will be useful. You must only see through the body, mind, and world that appear before you and realize that they are all insubstantial. Like imaginary reflectionsóthey are the same as images in the mirror or moon reflected in the water. Hear all sounds and voices like wind passing through the forest; perceive all objects as drifting clouds in the sky. Everything is in a constant state of flux; everything is illusory and insubstantial. Not only is the external world like this, but your own deluded thoughts, emotional discriminations of the mind, and all the seeds of passion, habit tendencies, as well as all vexations are also groundless and insubstantial.

If you can thus engage in contemplation, then whenever a thought arises, you should find its source. Never haphazardly allow it to pass you by [without seeing through it]. Do not be deceived by it! If this is how you work, then you will be doing some genuine practice. Do not try to gather up some abstract and intellectual view on it or try to fabricate some cleaver understanding about it. Still, to even speak about practice is really like the last alternative. For example, in the use of weapons, they are really not auspicious objects! But they are used as the last alternative [in battles]. The ancient ones spoke about investigating Chan and bringing forth the huatou. These, too are last alternatives. Even though there are innumerable gong ans, only by using the huatou, "Who is reciting the Buddhaís name?" can you derive power from it easily enough amidst vexing situations. Even though you can easily derive power from it, [this huatou] is merely a [broken] tile for knocking down doors. Eventually you will have to throw it away. Still, you must use it for now. If you plan to use a huatou for your practice, you must have faith, unwavering firmness, and perseverance. You must not have the least bit of hesitation and uncertainty. Also, you must not be one way today and another tomorrow. You should not be concerned that you will not be enlightened, nor should you feel that this huatou is not profound enough! All of these thoughts are just hindrances. I must speak of these now so that you will not give rise to doubt and suspicion when you are confronted [by difficulties].

If you can derive power from your power, the external world will not influence you. However, internally your mind may give rise to much frantic distraction for [seemingly] no reason. Sometimes desire and lust well up; sometime restlessness comes in. Numerous hindrances can arise inside of you making you feel mentally and physically exhausted. You will not know what to do. These are all of the karmic propensities that have been stored inside your eighth-consciousness for innumerable eons. Today, due to your energetic practice, they will all come out. At that critical point, you must be able to discern and see through them then pass beyond [these obstacles]. Never be controlled and manipulated by them and most of all, never take them to be real. At that point, you must refresh your spirit and arouse your courage and diligence then bring forth this existential concern with your investigation of the huatou. Fix your attention at the point from which thoughts arise and continuously push forward on and on and ask, "Originally there is nothing inside of me, so where does the [obstacle] come from? What is it?" You must be determined to find out the bottom of this matter. Pressing on just like this, killing every [delusion in sight,] without leaving a single trace until even the demons and spirits burst out in tears. If you can practice like this, naturally good news will come to you.

If you can smash through a single thought, then all deluded thinking will suddenly be stripped off. You will feel like a flower in the sky that casts no shadows, or like a bright sun emitting boundless light, or like a limpid pond, transparent and clear. After experiencing this, there will be immeasurable feelings of light and ease, as well as a sense of liberation. This is a sign of deriving power from practice for beginners. There is nothing marvelous or extraordinary about it. Do not rejoice and wallow in this ravishing experience. If you do, then the Mara of Joy will possess you and you will have gained another kind of obstruction! Concealed within the storehouse consciousness are your deep-rooted habit tendencies and seeds of passion. If your practice of huatou is not taking effect, or that youíre unable to contemplate and illuminate your mind, or youíre simply incapable of applying yourself to the practice, then you should practice prostrations, read the sutras, and engage yourself in repentance. You may also recite mantras to receive the secret seal of the Buddhas; it will alleviate your hindrances. This is because all the secret mantras are the seals of the Buddhasí diamond mind. When you use them, it is like holding an indestructible diamond thunderbolt that can shatter everything. Whatever comes close to it will be demolished into dust motes. The essence of all the esoteric teachings of all Buddhas and ancestral masters are contained in the mantras. Therefore, it is said that, "All Tathagatas in the ten directions attained unsurpassable and correct perfect enlightenment through such mantras." Even though the Buddhas have said this clearly, the lineage ancestral masters, fearing that these words may be misunderstood, have kept this knowledge a secret and do not use this method. Nevertheless, in order to derive power from using a mantra, you must practice it regularly after a long and extensive period of time. Yet, even so, you should never anticipate or seek miraculous response from using it.

III. Understanding-enlightenment

and Actualized-enlightenment

There are those who are first enlightened then engage in practice, and there are others who first practice and then get enlightened. Also, there is a difference with understanding-enlightenment and actualized-enlightenment.

Those who understand their minds after hearing the spoken teaching from the Buddhas and ancestral masters reach an understanding-enlightenment. In most cases, these people fall into views and knowledge. Confronted by all circumstances, they will not be able to make use of what they have come to know. Their minds and the external objects are in opposition. There is neither oneness nor harmony. Thus, they face obstacles all the time. [What they have realized] is called "prajna in semblance" and is not from genuine practice.

Actualized-enlightenment results from solid and sincere practice when you reach an impasse where the mountains are barren and waters are exhausted. Suddenly, [at the moment when] a thought stops, you will thoroughly perceive your own mind. At this time, you will feel as though you have personally seen your own father at a crossroadóthere is no doubt about it! It is like you yourself drinking water. Whether the water is cold or warm, only you will know, and it is not something you can describe to others. This is genuine practice and true enlightenment. Having had such experience, you can integrate it with all situations of life and purify, as well as relinquish, the karma that has already manifested, the stream of your consciousness, your deluded thinking and emotional conceptions until everything fuses into the One True [enlightened] Mind. This is actualized-enlightenment.

This state of actualized-enlightenment can be further divided into shallow and profound realizations. If you exert your efforts at the root [of your existence], smashing away the cave of the eighth consciousness, and instantaneously overturn the den of fundamental ignorance, with one leap directly enter [the realm of enlightenment], then there is nothing further for you to learn. This is having supreme karmic roots. Your actualization will be profound indeed. The depth of actualization for those who practice gradually, [on the other hand,] will be shallow.

The worst thing is to be self-satisfied with little [experiences]. Never allow yourself to fall into the dazzling experiences that arise from your sensory gates. Why? Because your eighth consciousness has not yet been crushed, so whatever you experience or do will be [conditioned] by your [deluded] consciousness and senses. If you think that this [consciousness] is real, then it is like mistaking a thief to be your own son! The ancient one has said, "Those who engage in practice do not know what is real because until now they have taken their consciousness [to be true]; what a fool takes to be his original face is actually the fundamental cause of birth and death." This is the barrier that you must pass through.

So called sudden enlightenment and gradual practice refers to one who has experienced a thorough enlightenment but, still has remnant habit tendencies that are not instantaneously purified. For these people, they must, implement the principles from their enlightenment that they have realized to face all circumstances of life and, bring forth the strength from their contemplation and illumination to experience their minds in difficult situations. When one portion of their experience in such situations accords[with the enlightened way], they will have actualized one portion of the Dharmakaya. When they dissolve away one portion of their deluded thinking, that is the degree to which their fundamental wisdom manifests. What is critical is seamless continuity in the practice. [For these people,] it is much more effective when they practice in different real life situations.

Comments by the Translator

Hanshan Deqing [1546-1623] is considered one of the four most eminent Buddhist monks in the late Ming Dynasty [1368-1644] partly for his social-political interactions with Ming court, exegesis of Buddhist texts, and most importantly, for his Chan practice. In this short introduction, I will only comment briefly on the last aspects on his contributions to Chinese Buddhism.

Even at age seven, Hanshan had existential concerns about life and death. These thoughts had led him to leave the household life and pursue a life of Buddhist training already at age nine. At the age of 19, he was ordained as a Buddhist monk.

In all of the history of Chan, there is not a single master that has written in such detail about his own practice and experiences, especially in describing the enlightened state of mind. According to a compiled record, The Dream Roaming of Great Master Hanshan, he had numerous and extraordinary enlightenment experiences. His first experience was during a Dharma lecture when he heard the profound teaching on the interpenetration of phenomena as taught in the Avatamsaka Sutra and the treatise, The Ten Wondrous Gates. He experienced another deep enlightenment experience sometime later when at Mt. Wu Tai he read the treatise by an early Chinese Madhyamika monk called Things do not Move. According to the record, Hanshan served as proofreader of the Book of Chao, the source of Things do not Move. Hanshan came across the stories of a Bramacharin who had left home in his youth and returned when he was white-haired. When people saw him, the neighbors asked, "Is that man [whom we know] still living today?" The Bramacharin replied, "I look like that man of the past, but I am not he." On reading this story ,, Hanshan suddenly understood that all things do not come and go. When he got up from his seat and walked around, he did not see things in motion. When he opened the window blind, suddenly a wind blew the trees in the yard, and the leaves flew all over the sky. However, he did not see any signs of motion. When he went to urinate, he still did not see signs of flowing. He understood what the text spoke of as, "Streams and rivers run into the ocean and yet there is no flowing." At this time, Hanshan shattered all doubt and existential concerns about birth and death. He wrote the following poem:

Life and death, day and night;

Water flows and flowers fall.

Only today, I know that

My nose points downward!

The next day when another great Chan Master, Miaofeng, saw him, he knew that Hanshan was different and asked him whether anything has happened. Hanshan replied, " Last night I saw two iron oxen fighting with each other next to the river bank. They both fell in the river. Since then, I have not heard anything about them." Miaofeng rejoiced and congratulated him.

Still, on another occasion, after a meal, Hanshan walked in the mountains and experienced a profound state of samadhi while standing. In the record, it described that suddenly he lost all consciousness of his body and mind. He experienced everything, the whole universe, as contained in a great perfect mirror-like mind. Mountains and rivers all reflected in it. After he came out of that experience, he wrote the following verse:

In an instant of thought, this chaotic mind is put to rest.

Internally and externally, the sense faculties and objects

Became empty and clear.

Overturning the bodyóemptiness is now shattered.

The myriad forms and appearances arise and extinguish

[in their own accord].

These are just some of his experiences recorded in The Dream Roaming of Great Master Hanshan. The instructions on practice that I have translated here are from the second fascicle of this record. The original text had no titles but were letters written to a lay practitioner on Chan practice.

Hanshan was also a prolific writer whose published works ranging from commentaries on Buddhist sutras and treatises, to secular poems, reached the length of 8,300 pages. In The Dream Roaming of Great Master Hanshan, there are 55 chuan, or books, covering over 3,000 pages. His commentaries on the Supplement to the Tripitaka consist of 119 chuan, covering over 1,200 large pages printed on both sides. Like other Ming Dynasty Buddhist monks, he also wrote many commentaries on non-Buddhist works such as Lao Zi and Zhuang Zi, as well as other Taoist and Confucian text.

His contributions to Chinese Buddhism lies in his exemplary personality and his striving toward liberation, especially in an age of mismanaged government, corruption, internal oppression, and the external vulnerability of the Ming Dynasty. Although his Buddhist commentary is not particularly original, the strength of his writing comes from his active approach in reviving and popularizing Buddhism, and in the way he responded to the times in which he lived.

From all that we know of Hanshan, we can conclude that he was a great master who gave equal weight to doctrine and practice, as well as to the revival of Chinese Buddhism.

弘一大師講演錄

0 comments Published by Panna Padipa-Light of Wisdom and Compassion on Wednesday, January 31, 2007 at 2:57 AM

◎佛法學習初步

戊寅十月八日在安海金墩宗祠講

佛法宗派大概,前已略說。

或謂高深教義,難解難行,非利根上智不能承受。若我輩常人欲學習佛法者,未知有何法門,能使人人易解,人人易行,毫無困難,速獲實益耶?

案佛法寬廣,有淺有深。故古代諸師,皆判「教相」以區別之。依唐圭峰禪師所撰華嚴原人論中,判立五教:

一、人天教

二、小乘教

三、大乘法相教

四、大乘破相教

五、一乘顯性教

以此五教,分別淺深。若我輩常人易解易行者,唯有「人天教」也。其他四教,義理高深,甚難瞭解。即能瞭解,亦難實行。故欲普及社會,又可補助世法,以挽救世道人心,應以「人天教」最為合宜也。

人天教由何而立耶?

常人醉生夢死,謂富貴貧賤吉凶禍福皆由命定,不解因果報應。或有解因果報應者,亦唯知今生之現報而已。若如是者,現生有惡人富而善人貧,惡人壽而善人夭,惡人多子孫而善人絕嗣,是何故歟?因是佛為此輩人,說三世業報,善惡因果,即是人天教也。今就三世業報及善惡因果分為二章詳述之。

一、三世業報

三世業報者,現報、生報、後報也。

一、現報:今生作善惡,今生受報。

二、生報:今生作善惡,次一生受報。

三、後報:今生作善惡,次二三生乃至未來多生受報。

由是而觀,則惡人富、善人貧等,決不足怪。吾人唯應力行善業,即使今生不獲良好之果報來生再來生等必能得之。萬勿因行善而反遇逆境,遂妄謂行善無有果報也。

二、善惡因果

善惡因果者,惡業、善業、不動業此三者是其因,果報有六,即六道也。

惡業善業,其數甚多,約而言之,各有十種,如下所述。不動業者,即修習上品十善,復能深修禪定也。

今以三因六果列表如下:

一、惡業

二、善業

三、不動業

┌上品……地獄

┼中品……畜生

└下品……鬼

┌下品……阿修羅

┼中品……人

└上品……欲界天

┌次品……色界天

┤

└上品……無色界天

───┐

───┤

───┤

───┼六道

───┤

┬天─┘

┤

│

┘

今復舉惡業、善業別述如下:

惡業有十種。

一、殺生

二、偷盜

三、邪淫

四、妄言

五、兩舌

六、惡口

七、綺語

八、慳貪

九、瞋恚

十、邪見

造惡業者,因其造業重輕,而墮地獄、畜生、鬼道之中。受報既盡,幸生人中,猶有餘報。今依華嚴經所載者,錄之如下。若諸「論」中,尚列外境多種,今不別錄。

一、殺生……短命、多病

二、偷盜……貧窮、其財不得自在

三、邪淫……妻不貞良、不得隨意眷屬

四、妄言……多被誹謗、為他所誑

五、兩舌……眷屬乖離、親族弊惡

六、惡口……常聞惡聲、言多諍訟

七、綺語……言無人受、語不明了

八、慳貪……心不知足、多欲無厭

九、瞋恚……常被他人求其長短、恒被於他之所惱害

十、邪見……生邪見家、其心諂曲

善業有十種。下列不殺生等,止惡即名為善。復依此而起十種行善,即救護生命等也。

一、不殺生:救護生命

二、不偷盜:給施資財

三、不邪淫:遵修梵行

四、不妄言:說誠實言

五、不兩舌:和合彼此

六、不惡口:善言安慰

七、不綺語:作利益語

八、不慳貪:常懷捨心

九、不瞋恚:恒生慈憫

十、不邪見:正信因果

造善業者,因其造業輕重而生於阿修羅人道欲界天中。所感之餘報,與上所列惡業之餘報相反。如不殺生則長壽無病等類推可知。

由是觀之,吾人欲得諸事順遂,身心安樂之果報者,應先力修善業,以種善因。若唯一心求好果報,而決不肯種少許善因,是為大誤。譬如農夫,欲得米穀,而不種田,人皆知其為愚也。

故吾人欲諸事順遂,身心安樂者,須努力培植善因。將來或遲或早,必得良好之果報。古人云:「禍福無不自己求之者」,即是此意也。

以上所說,乃人天教之大義。

唯修人天教者,雖較易行,然報限人天,非是出世。故古今諸大善知識,盡力提倡「淨土法門」,即前所說之佛法宗派大概中之「淨土宗」。令無論習何教者,皆兼學此「淨土法門」,即能獲得最大之利益。「淨土法門」雖隨宜判為「一乘圓教」,但深者見深,淺者見淺,即唯修人天教者亦可兼學,所謂「三根普被」也。

在此講說三日已竟。以此功德,惟願世界安寧,眾生歡樂,佛日增輝,法輪常轉。

◎佛教之簡易修持法

己卯四月十六日在永春桃源殿講李芳遠記

我到永春的因緣,最初發起,在三年之前。性願老法師常常勸我到此地來,又常提起普濟寺是如何如何的好。

兩年以前的春天,我在南普陀講律圓滿以後,妙慧師便到廈門請我到此地來。那時因為學律的人要隨行的太多,而普濟寺中設備未廣,不能夠收容,不得已而中止。是為第一次欲來未果。

是年的冬天,有位善興師,他持著永春諸善友一張請帖,到廈門萬石岩去,要接我來永春。那時因為已先應了泉州草庵之請,故不能來永春。是為第二次欲來未果。

去年的冬天,妙慧師再到草庵來接。本想隨請前來,不意過泉州時,又承諸善友挽留,不得已而延期至今春。是為第三次欲來未果。

直至今年半個月以前,妙慧師又到泉州勸請,是為第四次。因大眾既然有如此的盛意,故不得不來。其時在泉州各地講經,很是忙碌,因此又延擱了半個多月。今得來到貴處,和諸位善友相見,我心中非常的歡喜。自三年前就想到此地來,屢次受了事情所阻,現在得來,滿其多年的夙願,更可說是十分的歡喜了。

今天承諸位善友請我演講。我以為談玄說妙,雖然極為高尚,但於現在行持終覺了不相涉。所以今天我所講的,且就常人現在即能實行的,約略說之。

因為專尚談玄說妙,譬如那饑餓的人,來研究食譜,雖山珍海錯之名,縱橫滿紙,如何能夠充饑。倒不如現在得到幾種普通的食品,即可入口。得充一飽,才於實事有濟。

以下所講的,分為三段。

一、深信因果

因果之法,雖為佛法入門的初步,但是非常的重要,無論何人皆須深信。何謂因果?因者好比種子,下在田中,將來可以長成為果實。果者譬如果實,自種子發芽,漸漸地開花結果。

我們一生所作所為,有善有惡,將來報應不出下列:

桃李種 長成為桃李——作善報善

荊棘種 長成為荊棘——作惡報惡

所以我們要避凶得吉,消災得福,必須要厚植善因,努力改過遷善,將來才能夠獲得吉祥福德之好果。如果常作惡因,而要想免除凶禍災難,哪里能夠得到呢?

所以第一要勸大眾深信因果了知善惡報應,一絲一毫也不會差的。

二、發菩提心

「菩提」二字是印度的梵語,翻譯為「覺」,也就是成佛的意思。發者,是發起,故發菩提心者,便是發起成佛的心。為什麼要成佛呢?為利益一切眾生。須如何修持乃能成佛呢?須廣修一切善行。以上所說的,要廣修一切善行,利益一切眾生,但須如何才能夠徹底呢?須不著我相。所以發菩提心的人,應發以下之三種心:

一、大智心:不著我相 此心雖非凡夫所能發,亦應隨分觀察。

二、大願心:廣修善行。

三、大悲心:救眾生苦。

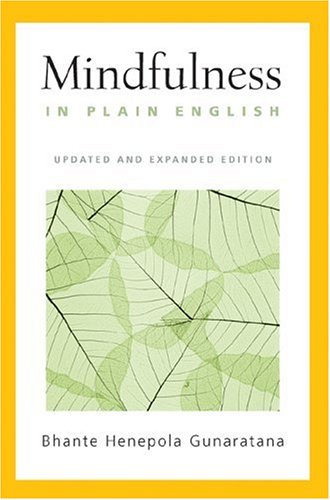

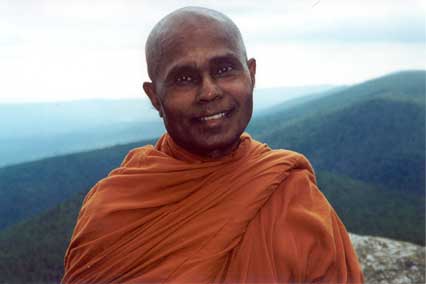

H. Gunaratana Mahathera

Chapter 13

Mindfulness (Sati)

Mindfulness is the English translation of the Pali word Sati. Sati is an activity. What exactly is that? There can be no precise answer, at least not in words. Words are devised by the symbolic levels of the mind and they describe those realities with which symbolic thinking deals. Mindfulness is pre-symbolic. It is not shackled to logic. Nevertheless, Mindfulness can be experienced -- rather easily -- and it can be described, as long as you keep in mind that the words are only fingers pointing at the moon. They are not the thing itself. The actual experience lies beyond the words and above the symbols. Mindfulness could be describes in completely different terms than will be used here and each description could still be correct.

Mindfulness is a subtle process that you are using at this very moment. The fact that this process lies above and beyond words does not make it unreal--quite the reverse. Mindfulness is the reality which gives rise to words--the words that follow are simply pale shadows of reality. So, it is important to understand that everything that follows here is analogy. It is not going to make perfect sense. It will always remain beyond verbal logic. But you can experience it. The meditation technique called Vipassana (insight) that was introduced by the Buddha about twenty-five centuries ago is a set of mental activities specifically aimed at experiencing a state of uninterrupted Mindfulness.

When you first become aware of something, there is a fleeting instant of pure awareness just before you conceptualize the thing, before you identify it. That is a stage of Mindfulness. Ordinarily, this stage is very short. It is that flashing split second just as you focus your eyes on the thing, just as you focus your mind on the thing, just before you objectify it, clamp down on it mentally and segregate it from the rest of existence. It takes place just before you start thinking about it--before your mind says, "Oh, it's a dog." That flowing, soft-focused moment of pure awareness is Mindfulness. In that brief flashing mind-moment you experience a thing as an un-thing. You experience a softly flowing moment of pure experience that is interlocked with the rest of reality, not separate from it. Mindfulness is very much like what you see with your peripheral vision as opposed to the hard focus of normal or central vision. Yet this moment of soft, unfocused, awareness contains a very deep sort of knowing that is lost as soon as you focus your mind and objectify the object into a thing. In the process of ordinary perception, the Mindfulness step is so fleeting as to be unobservable. We have developed the habit of squandering our attention on all the remaining steps, focusing on the perception, recognizing the perception, labeling it, and most of all, getting involved in a long string of symbolic thought about it. That original moment of Mindfulness is rapidly passed over. It is the purpose of the above mentioned Vipassana (or insight) meditation to train us to prolong that moment of awareness.

When this Mindfulness is prolonged by using proper techniques, you find that this experience is profound and it changes your entire view of the universe. This state of perception has to be learned, however, and it takes regular practice. Once you learn the technique, you will find that Mindfulness has many interesting aspects.

The Characteristics of Mindfulness

Mindfulness is mirror-thought. It reflects only what is presently happening and in exactly the way it is happening. There are no biases.

Mindfulness is non-judgmental observation. It is that ability of the mind to observe without criticism. With this ability, one sees things without condemnation or judgment. One is surprised by nothing. One simply takes a balanced interest in things exactly as they are in their natural states. One does not decide and does not judge. One just observes. Please note that when we say "One does not decide and does not judge," what we mean is that the meditator observes experiences very much like a scientist observing an object under the microscope without any preconceived notions, only to see the object exactly as it is. In the same way the meditator notices impermanence, unsatisfactoriness and selflessness.

It is psychologically impossible for us to objectively observe what is going on within us if we do not at the same time accept the occurrence of our various states of mind. This is especially true with unpleasant states of mind. In order to observe our own fear, we must accept the fact that we are afraid. We can't examine our own depression without accepting it fully. The same is true for irritation and agitation, frustration and all those other uncomfortable emotional states. You can't examine something fully if you are busy reflecting its existence. Whatever experience we may be having, Mindfulness just accepts it. It is simply another of life's occurrences, just another thing to be aware of. No pride, no shame, nothing personal at stake--what is there, is there.

Mindfulness is an impartial watchfulness. It does not take sides. It does not get hung up in what is perceived. It just perceives. Mindfulness does not get infatuated with the good mental states. It does not try to sidestep the bad mental states. There is no clinging to the pleasant, no fleeing from the unpleasant. Mindfulness sees all experiences as equal, all thoughts as equal, all feelings as equal. Nothing is suppressed. Nothing is repressed. Mindfulness does not play favorites.

Mindfulness is nonconceptual awareness. Another English term for Sati is 'bare attention'. It is not thinking. It does not get involved with thought or concepts. It does not get hung up on ideas or opinions or memories. It just looks. Mindfulness registers experiences, but it does not compare them. It does not label them or categorize them. It just observes everything as if it was occurring for the first time. It is not analysis which is based on reflection and memory. It is, rather, the direct and immediate experiencing of whatever is happening, without the medium of thought. It comes before thought in the perceptual process.

Mindfulness is present time awareness. It takes place in the here and now. It is the observance of what is happening right now, in the present moment. It stays forever in the present, surging perpetually on the crest of the ongoing wave of passing time. If you are remembering your second-grade teacher, that is memory. When you then become aware that you are remembering your second-grade teacher, that is mindfulness. If you then conceptualize the process and say to yourself, "Oh, I am remembering", that is thinking.

Mindfulness is non-egoistic alertness. It takes place without reference to self. With Mindfulness one sees all phenomena without references to concepts like 'me', 'my' or 'mine'. For example, suppose there is pain in your left leg. Ordinary consciousness would say, "I have a pain." Using Mindfulness, one would simply note the sensation as a sensation. One would not tack on that extra concept 'I'. Mindfulness stops one from adding anything to perception, or subtracting anything from it. One does not enhance anything. One does not emphasize anything. One just observes exactly what is there--without distortion.

Mindfulness is goal-less awareness. In Mindfulness, one does not strain for results. One does not try to accomplish anything. When one is mindful, one experiences reality in the present moment in whatever form it takes. There is nothing to be achieved. There is only observation.

Mindfulness is awareness of change. It is observing the passing flow of experience. It is watching things as they are changing. it is seeing the birth, growth, and maturity of all phenomena. It is watching phenomena decay and die. Mindfulness is watching things moment by moment, continuously. It is observing all phenomena--physical, mental or emotional--whatever is presently taking place in the mind. One just sits back and watches the show. Mindfulness is the observance of the basic nature of each passing phenomenon. It is watching the thing arising and passing away. It is seeing how that thing makes us feel and how we react to it. It is observing how it affects others. In Mindfulness, one is an unbiased observer whose sole job is to keep track of the constantly passing show of the universe within. Please note that last point. In Mindfulness, one watches the universe within. The meditator who is developing Mindfulness is not concerned with the external universe. It is there, but in meditation, one's field of study is one's own experience, one's thoughts, one's feelings, and one's perceptions. In meditation, one is one's own laboratory. The universe within has an enormous fund of information containing the reflection of the external world and much more. An examination of this material leads to total freedom.

Mindfulness is participatory observation. The meditator is both participant and observer at one and the same time. If one watches one's emotions or physical sensations, one is feeling them at that very same moment. Mindfulness is not an intellectual awareness. It is just awareness. The mirror-thought metaphor breaks down here. Mindfulness is objective, but it is not cold or unfeeling. It is the wakeful experience of life, an alert participation in the ongoing process of living.

Mindfulness is an extremely difficult concept to define in words -- not because it is complex, but because it is too simple and open. The same problem crops up in every area of human experience. The most basic concept is always the most difficult to pin down. Look at a dictionary and you will see a clear example. Long words generally have concise definitions, but for short basic words like 'the' and 'is', definitions can be a page long. And in physics, the most difficult functions to describe are the most basic--those that deal with the most fundamental realities of quantum mechanics. Mindfulness is a pre-symbolic function. You can play with word symbols all day long and you will never pin it down completely. We can never fully express what it is. However, we can say what it does.

Three Fundamental Activities

There are three fundamental activities of Mindfulness. We can use these activities as functional definitions of the term: (a) Mindfulness reminds us of what we are supposed to be doing; (b) it sees things as they really are; and (c) it sees the deep nature of all phenomena. Let's examine these definitions in greater detail.

(a) Mindfulness reminds you of what you are supposed to be doing . In meditation, you put your attention on one item. When your mind wanders from this focus, it is Mindfulness that reminds you that your mind is wandering and what you are supposed to be doing. It is Mindfulness that brings your mind back to the object of meditation. All of this occurs instantaneously and without internal dialogue. Mindfulness is not thinking. Repeated practice in meditation establishes this function as a mental habit which then carries over into the rest of your life. A serious meditator pays bare attention to occurrences all the time, day in, day out, whether formally sitting in meditation or not. This is a very lofty ideal towards which those who meditate may be working for a period of years or even decades. Our habit of getting stuck in thought is years old, and that habit will hang on in the most tenacious manner. The only way out is to be equally persistent in the cultivation of constant Mindfulness. When Mindfulness is present, you will notice when you become stuck in your thought patterns. It is that very noticing which allows you to back out of the thought process and free yourself from it. Mindfulness then returns your attention to its proper focus. If you are meditating at that moment, then your focus will be the formal object of meditation. If your are not in formal meditation, it will be just a pure application of bare attention itself, just a pure noticing of whatever comes up without getting involved--"Ah, this comes up...and now this, and now this... and now this".

Mindfulness is at one and the same time both bare attention itself and the function of reminding us to pay bare attention if we have ceased to do so. Bare attention is noticing. It re- establishes itself simply by noticing that it has not been present. As soon as you are noticing that you have not been noticing, then by definition you are noticing and then you are back again to paying bare attention.

Mindfulness creates its own distinct feeling in consciousness. It has a flavor--a light, clear, energetic flavor. Conscious thought is heavy by comparison, ponderous and picky. But here again, these are just words. Your own practice will show you the difference. Then you will probably come up with your own words and the words used here will become superfluous. Remember, practice is the thing.

(b) Mindfulness sees things as they really are. Mindfulness adds nothing to perception and it subtracts nothing. It distorts nothing. It is bare attention and just looks at whatever comes up. Conscious thought pastes things over our experience, loads us down with concepts and ideas, immerses us in a churning vortex of plans and worries, fears and fantasies. When mindful, you don't play that game. You just notice exactly what arises in the mind, then you notice the next thing. "Ah, this...and this...and now this." It is really very simple.

(c) Mindfulness sees the true nature of all phenomena. Mindfulness and only Mindfulness can perceive the three prime characteristics that Buddhism teaches are the deepest truths of existence. In Pali these three are called Anicca (impermanence), Dukkha (unsatisfactoriness), and Anatta (selflessness--the absence of a permanent, unchanging, entity that we call Soul or Self). These truths are not present in Buddhist teaching as dogmas demanding blind faith. The Buddhists feel that these truths are universal and self-evident to anyone who cares to investigate in a proper way. Mindfulness is the method of investigation. Mindfulness alone has the power to reveal the deepest level of reality available to human observation. At this level of inspection, one sees the following: (a) all conditioned things are inherently transitory; (b) every worldly thing is, in the end, unsatisfying; and (c) there are really no entities that are unchanging or permanent, only processes.

Mindfulness works like and electron microscope. That is, it operates on so fine a level that one can actually see directly those realities which are at best theoretical constructs to the conscious thought process. Mindfulness actually sees the impermanent character of every perception. It sees the transitory and passing nature of everything that is perceived. It also sees the inherently unsatisfactory nature of all conditioned things. It sees that there is no sense grabbing onto any of these passing shows. Peace and happiness cannot be found that way. And finally, Mindfulness sees the inherent selflessness of all phenomena. It sees the way that we have arbitrarily selected a certain bundle of perceptions, chopped them off from the rest of the surging flow of experience and then conceptualized them as separate, enduring, entities. Mindfulness actually sees these things. It does not think about them, it sees them directly.

When it is fully developed, Mindfulness sees these three attributes of existence directly, instantaneously, and without the intervening medium of conscious thought. In fact, even the attributes which we just covered are inherently unified. They don't really exist as separate items. They are purely the result of our struggle to take this fundamentally simple process called Mindfulness and express it in the cumbersome and inadequate thought symbols of the conscious level. Mindfulness is a process, but it does not take place in steps. It is a holistic process that occurs as a unit: you notice your own lack of Mindfulness; and that noticing itself is a result of Mindfulness; and Mindfulness is bare attention; and bare attention is noticing things exactly as they are without distortion; and the way they are is impermanent (Anicca) , unsatisfactory (Dukkha), and selfless (Anatta). It all takes place in the space of a few mind-moments. This does not mean, however, that you will instantly attain liberation (freedom from all human weaknesses) as a result of your first moment of Mindfulness. Learning to integrate this material into your conscious life is another whole process. And learning to prolong this state of Mindfulness is still another. They are joyous processes, however, and they are well worth the effort.

Mindfulness (Sati) and Insight (Vipassana) Meditation

Mindfulness is the center of Vipassana Meditation and the key to the whole process. It is both the goal of this meditation and the means to that end. You reach Mindfulness by being ever more mindful. One other Pali word that is translated into English as Mindfulness is Appamada , which means non-negligence or an absence of madness. One who attends constantly to what is really going on in one's mind achieves the state of ultimate sanity.

The Pali term Sati also bears the connotation of remembering. It is not memory in the sense of ideas and pictures from the past, but rather clear, direct, wordless knowing of what is and what is not, of what is correct and what is incorrect, of what we are doing and how we should go about it. Mindfulness reminds the meditator to apply his attention to the proper object at the proper time and to exert precisely the amount of energy needed to do the job. When this energy is properly applied, the meditator stays constantly in a state of calm and alertness. As long as this condition is maintained, those mind-states call "hindrances" or "psychic irritants" cannot arise--there is no greed, no hatred, no lust or laziness. But we all are human and we do err. Most of us err repeatedly. Despite honest effort, the meditator lets his Mindfulness slip now and then and he finds himself stuck in some regrettable, but normal, human failure. It is Mindfulness that notices that change. And it is Mindfulness that reminds him to apply the energy required to pull himself out. These slips happen over and over, but their frequency decreases with practice. Once Mindfulness has pushed these mental defilements aside, more wholesome states of mind can take their place. Hatred makes way for loving kindness, lust is replaced by detachment. It is Mindfulness which notices this change, too, and which reminds the Vipassana meditator to maintain that extra little mental sharpness needed to keep these more desirable states of mind. Mindfulness makes possible the growth of wisdom and compassion. Without Mindfulness they cannot develop to full maturity.

Deeply buried in the mind, there lies a mental mechanism which accepts what the mind perceives as beautiful and pleasant experiences and rejects those experiences which are perceived as ugly and painful. This mechanism gives rise to those states of mind which we are training ourselves to avoid--things like greed, lust, hatred, aversion, and jealousy. We choose to avoid these hindrances, not because they are evil in the normal sense of the word, but because they are compulsive; because they take the mind over and capture the attention completely; because they keep going round and round in tight little circles of thought; and because they seal us off from living reality.

These hindrances cannot arise when Mindfulness is present. Mindfulness is attention to present time reality, and therefore, directly antithetical to the dazed state of mind which characterizes impediments. As meditators, it is only when we let our Mindfulness slip that the deep mechanisms of our mind take over -- grasping, clinging and rejecting. Then resistance emerges and obscures our awareness. We do not notice that the change is taking place -- we are too busy with a thought of revenge, or greed, whatever it may be. While an untrained person will continue in this state indefinitely, a trained meditator will soon realize what is happening. It is Mindfulness that notices the change. It is Mindfulness that remembers the training received and that focuses our attention so that the confusion fades away. And it is Mindfulness that then attempts to maintain itself indefinitely so that the resistance cannot arise again. Thus, Mindfulness is the specific antidote for hindrances. It is both the cure and the preventive measure.

Fully developed Mindfulness is a state of total non-attachment and utter absence of clinging to anything in the world. If we can maintain this state, no other means or device is needed to keep ourselves free of obstructions, to achieve liberation from our human weaknesses. Mindfulness is non-superficial awareness. It sees things deeply, down below the level of concepts and opinions. This sort of deep observation leads to total certainty, and complete absence of confusion. It manifests itself primarily as a constant and unwavering attention which never flags and never turns away.

This pure and unstained investigative awareness not only holds mental hindrances at bay, it lays bare their very mechanism and destroys them. Mindfulness neutralizes defilements in the mind. The result is a mind which remains unstained and invulnerable, completely unaffected by the ups and downs of life.

-oOo-

(corrected by Pedro Ripa, ripa@cicese.mx , 01 June 2001)

《金刚经》的经题

0 comments Published by Panna Padipa-Light of Wisdom and Compassion on Wednesday, January 17, 2007 at 11:46 PM《金刚经》的经题是‘金刚般若波罗蜜’。这个‘般若’,没有适当的中国字可以翻,因此就翻译了它的音,而没有翻译它的意思。这是古时候译经家的一种规定。咱们国家没有适当的名词恰好跟这个‘般若’一样,但是这个音有点走了样,注了这个音,这个音还是接近的。要是翻译了意思,就是‘无上正等正觉’。有的翻译的是音,有的翻译的是意思。‘般若’就是音。因为我们中国没有适当的字相当于‘般若’,勉强叫做智慧。这很容易混,因此就需要‘般若’翻成中国的意思,就是深智慧或者大智慧,以区别于咱们一般所谓的智慧。尤其是要区别于咱们所谓的世智辩聪,这两个词的意思恰恰有天渊之别。我们如果把世智辩聪当作了般若,那就是禅宗的话:‘把驴鞍桥当作阿爹的下巴颌(铠Kai)了’。那个桥跟下巴颌没有共同之处,如果把般若体会成世间的学问、世间的聪明能干,那就大错特错了。因为世智辩聪是佛教所讲的‘八难’之一,学佛是有八种人是很困难学的:聋子、瞎子、哑巴......。哑巴,他就不能问话;如聋如盲,他就看不见、听不见。还有神经病等都属于‘八难’之一。这个世智辩聪是跟‘八难’并列的。我们有的时候常常不知道,有的人还以此自负,不知道这是一种缺点。所谓‘般若’既不是我们所说的智慧,也不是指学问,而是一个大智慧,极深的智慧。‘六度波罗蜜’里头前五度—布施、持戒、忍辱、精进、禅定,如果只是这前五度而没有般若的话,不能称为‘波罗蜜’。你只是布施,就是布施,不能成‘布施波罗蜜’。忍辱,只是忍辱,而不能成为‘忍辱波罗蜜’......波罗蜜是什么意思呢?翻译过来的意思就是‘彼岸到’。外国文法是倒过来说的,咱们的话就是‘到彼岸’。众生生生死死轮回不断,这生死是一岸。我们在这岸里头,八宝山一烧,又不知驴胎马腹哪里去了,轮回不休。现在大量的科学研究,证明这种轮回是事实!很多人都记得他前生的事情,还出了大量专书,是外国人写的书。生死这一岸是可怕的,我们死是很苦的,这个死是无穷尽的死。一个人说:‘我难过的要死’,那就是用这个‘死’来形容难过到极点了。这个死是极难过的,如果只死一回就空了,这事情也好办了,但是这种死是无穷尽的。而且这‘六道’里头还有‘三恶道’,‘三恶道’苦趣的时间就更长了,三途一报就是五千劫呀!释迦牟尼佛修精舍的时候,很多大阿罗汉看见蚂蚁就哭了。因为前一个佛在这说法,这些蚂蚁当时就是蚂蚁,它们一直到现在还是蚂蚁。你看前一个佛过后,另一个佛出世得多少年时间呀!可它们还是蚂蚁。所以堕入这种恶趣就很难得再从这恶趣里头出来呀!因为它结的缘只是这个缘,它思想里头只是这个东西,它就出不去了。所以这生死之岸很可怕。